- Published on

Closing the Gap: A Simple History of How We Interact with Computers

- Authors

- Name

- Sixing Tao

- @j0nathanta0

We interact with computers all the time. When we ask a voice assistant for the weather or tell an AI to write an email, we expect it to understand us. But how did we get here? The whole history of computers is a story about trying to close the gap between people and machines.

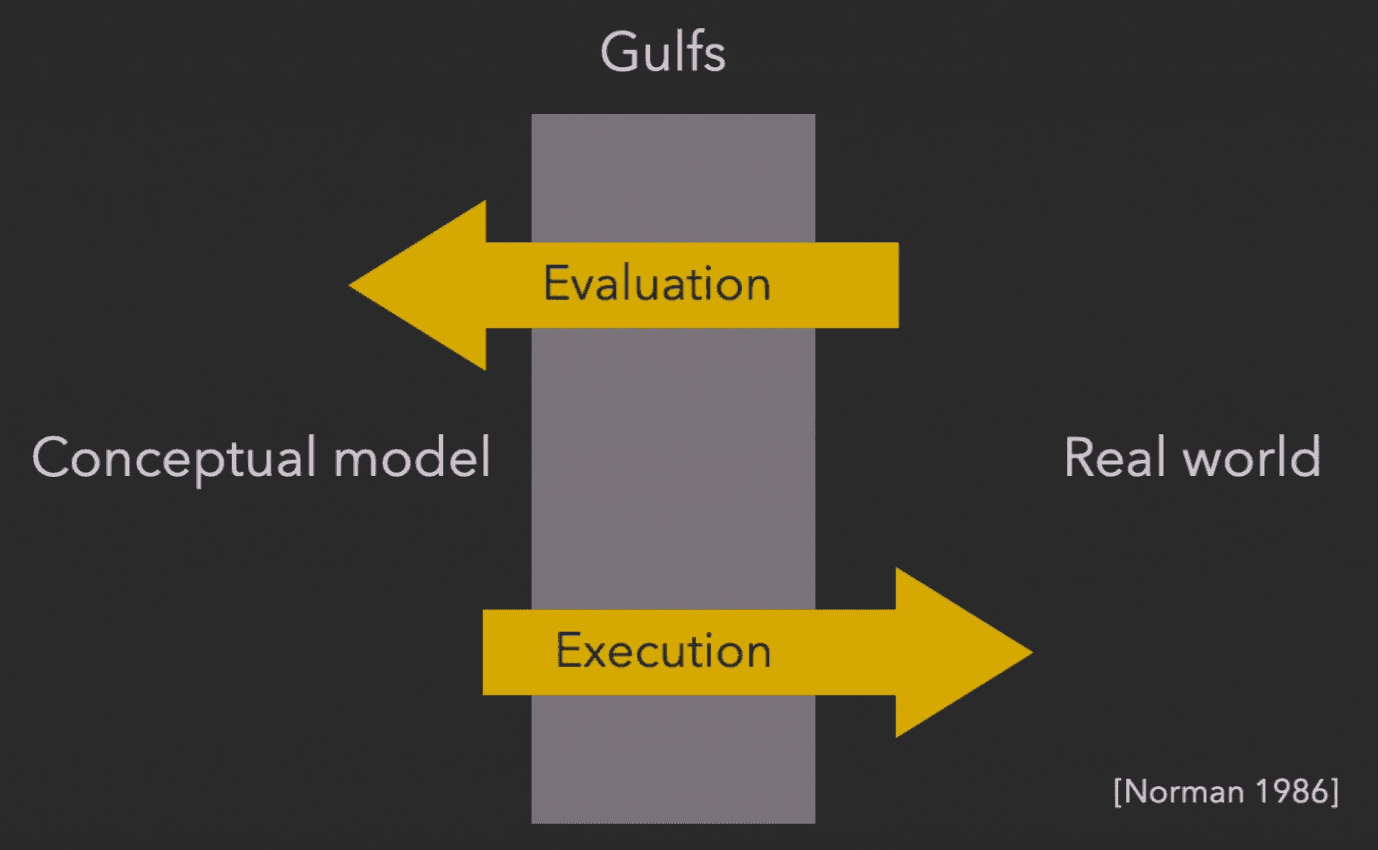

To understand this journey, we need a map. Luckily, the perfect one was created by computer scientist, Dr. Donald Norman. As a Human-Computer Interaction researcher, he identified two major gaps that exist between a person's mind and a machine's design.

As the original 1986 definition states:

The Gulf of Execution: This is the difference between a user's intentions and the allowable actions a system offers.

The Gulf of Evaluation: The amount of effort that the person must exert to interpret the state of the system and to determine how well the expectations and intentions have been met.

But where do these gaps come from? In his classic book, The Design of Everyday Things, Norman explained that they arise during a seven-stage cycle of action. This cycle is the engine of interaction, and the gulfs are the places where that engine can stall.

Before Anything Happens: The Spark

Form the Goal (Intention): It all starts here. This is the objective a person wants to achieve, existing purely in their mind. ("I want to make the title on this slide blue.")

From this starting point, the cycle unfolds in two main parts: doing (execution) and checking (evaluation).

Part 1: Doing (Bridging the Gulf of Execution)

This part covers the steps you take to act on your goal:

- Plan: You form a general plan to achieve the goal. ("Okay, I'll need to use the text formatting tools.")

- Specify: You translate that plan into specific, concrete steps. ("I'll select the title text, then find the 'Font Color' button, then click the blue square.")

- Perform: You physically execute those steps in the world. (You actually move the mouse, click, and drag.)

If a system's design makes it hard to plan, specify, or perform these actions, you've fallen into the Gulf of Execution. It’s the "How do I do it?" problem.

Part 2: Checking (Bridging the Gulf of Evaluation)

This part is about figuring out what happened as a result:

- Perceive: You observe the system's feedback. ("I see the text on the slide has changed color.")

- Interpret: You make sense of that feedback. ("I understand that the new color is blue.")

- Compare: You compare the new state to your original goal. ("Yes, the title is blue now. This matches what I wanted to do.")

If the system gives poor feedback, making it hard to perceive, interpret, or compare the result, you've fallen into the Gulf of Evaluation. It’s the "Did it work?" problem.

This seven-stage cycle is the foundation of interaction design. Every new technology, from the command line to AI, can be understood by how it tries to make this cycle easier and smoother.

Now, with this map in hand, we can look at how our relationship with computers has changed over five big stages.

Stage 1: The Monologue in the Dark (Batch Processing)

Imagine the computer rooms of the 1950s and 60s, dominated by room-sized mainframes like the IBM System/360. Interaction was an indirect, physical process: programmers would meticulously translate logic into a language of holes punched onto stiff paper cards, a technology inherited from Herman Hollerith's tabulating machines for the 1890 U.S. census. This was the era of batch processing, where you couldn't touch the machine yourself; instead, you'd hand your precious stack of cards—your "job"—to a professional operator who managed the queue. You would then walk away, returning hours or even days later to find a long, fan-folded printout of your results, and pray you hadn't made a single typo, which would force you to start the entire, painstaking process all over again.

The Gulf of Execution: An Act of Blind Faith

This gap was an abyss. The user had to perform Norman's entire execution cycle (Plan, Specify, Perform) perfectly in their mind, completely detached from the machine. The system's "allowable actions" were invisible rules in a manual, not options on a screen. A single typo in the Specify stage (a misplaced hole on a card) would invalidate the entire effort, but you wouldn't know it until much later. The cognitive load was immense because the entire interaction was a pre-scripted monologue sent into the void.

The Gulf of Evaluation: A Delayed Echo

This gap was equally vast. The feedback loop—the time between Perform and Perceive—was measured in hours or days. When the printout finally arrived, the user had to mentally reconstruct their original goal and actions from hours ago to Interpret the results. It was like shouting a question into a canyon and hearing a cryptic echo return the next day; the mental effort to connect the echo back to the original shout was enormous.

Stage 2: The First Conversation (The Command-Line Interface - CLI)

Then, the monolithic silence of the mainframe was shattered. Thanks to the magic of time-sharing systems in the 1960s, computers learned to multitask, allowing them to talk to many people at once through new devices called terminals. The one-way message sent on a punch card became a two-way dialogue typed on a keyboard and read on a glowing screen. For the first time, you could have a real-time "conversation" with a computer.

The Gulf of Execution: Learning a Secret Language

While the dialogue was now possible, the gap remained wide. The core challenge shifted from blind planning to rote memorization. The user's Plan ("I want to copy these files") was simple, but the Specify stage required translating that intent into the machine's strict, unforgiving syntax (cp -r source/ destination/). The system was like a powerful but pedantic genie: it would grant your wish perfectly if you knew the magic words, but a single misspoken syllable would render it inert, offering only a blunt "command not found."

The Gulf of Evaluation: The Dawn of Instant Feedback

This is where the revolution happened. The CLI dramatically bridged this gap by creating the first tight action-feedback loop. You could Perform an action (type a command, hit Enter) and instantly Perceive the result. The system's state was no longer a mystery. This immediacy made it trivial to Interpret the outcome and Compare it to the goal. For the first time, interaction felt like a turn-based conversation, not a message sent in a bottle. This solved the "Did it work?" problem in real-time.

Stage 3: The Visible Machine (The Graphical User Interface - GUI)

The next great leap wasn't about making the conversation better; it was about ending the need for one. The insight, born at Xerox PARC and perfected by Apple, was to build a powerful metaphor that everyone already understood: the desktop. Abstract directories became tangible folders; text files became paper documents. The machine's world was no longer a place you talked to, but a space you could inhabit. This gave birth to the GUI.

The Gulf of Execution: From Recall to Recognition

The GUI's biggest impact on the Gulf of Execution was changing the user's task from recall to recognition. Instead of having to remember a specific command from memory, the user could now see icons and menus and simply recognize the option they needed. This principle, known as Direct Manipulation, made many actions feel intuitive for the first time. However, the gulf didn't disappear; it just changed form. In complex software like Photoshop or Excel, the challenge became one of navigation. While all the tools were visible somewhere, the user had to find the right path through a series of menus, toolbars, and clicks to accomplish their goal. The question shifted from "What command do I type?" to "Which button do I need to click?".

The Gulf of Evaluation: The Two-Layered Feedback

The most subtle contribution of the GUI was splitting the Gulf of Evaluation into two distinct layers, clearly separating the machine's responsibility from the user's.

The Mechanical Gap - Almost Eliminated: This gap addresses the question, "Did the system correctly perform my action?" The GUI almost completely closes this gap with immediate, visible, and unambiguous feedback. This is the magic of "What You See Is What You Get" (WYSIWYG): when you click the "Bold" button, the text instantly becomes bold. In Norman's cycle, the loop from Perform -> Perceive -> Interpret is instantaneous and clear.

The Semantic Gap - Still Significant: This gap addresses the deeper question, "Does this result achieve my original Goal?" The system has perfectly executed the action "make it bold," but now it is your turn to perform the final step in Norman's cycle: Compare. You must compare the bolded text to your original, often vague, high-level goal—"to make this title look professional." This evaluation relies on your aesthetic sense, experience, and contextual judgment. The GUI can perfectly respond to your instructions, but it cannot read your intention.

Stage 4: The Conversation Resumes (Language User Interfaces - LUI)

After decades spent perfecting the visible, tangible world of the GUI, the next great leap felt like a radical return to the past. Interaction reverted to a conversation. This time, however, it wasn't the machine's rigid, unforgiving language we had to learn, but our own. Fueled by vast internet data and new neural network architectures, voice assistants and chatbots brought natural language interaction to the mainstream. The goal was no longer just to click on what you see, but to simply ask for what you want.

The Gulf of Execution: From "What do I click?" to "How should I ask?"

At first glance, LUI seems to have eliminated this gulf. The user no longer needs to Plan a series of steps or Specify them through menus. Instead, they can state their high-level Goal directly. However, the gulf merely transformed into a new, more subtle challenge: The Gulf of Expression. The burden on the user shifts from navigating a visible interface to formulating the perfect verbal or written prompt. An ambiguous or poorly phrased question leads to an incorrect result. The user must learn to translate their internal, often fuzzy, intent into precise language the AI can unambiguously act upon.

The Gulf of Evaluation: The Black Box Problem

This new evaluation crisis is often a direct result of the Gulf of Expression. For example, a user might ask a seemingly simple question like, "What were our profits last quarter?" This prompt, however, is deeply ambiguous. Does "profits" mean gross or net? Does "last quarter" follow the calendar or the fiscal year? The AI is forced to make an assumption to answer, and because its process is a black box, the user cannot Interpret which assumption was made. This extreme difficulty in interpretation gives rise to a new, more profound chasm:

- The Gulf of Trust. As the user tries to perform the final step of Comparing the answer to their goal, the core question is no longer just "Did it work?" but "Can I believe this answer at all?" This is the Semantic Gap from the GUI era, but taken to its absolute extreme. The fundamental challenge of the LUI is that it requires the user to take a leap of faith, a faith made necessary by the very ambiguity of the language it uses.

Stage 5: The Partner in Creation (Generative User Interface, GenUI)

This brings us to the current frontier of interaction, an emerging paradigm still being explored: the Generative User Interface (GenUI). It points toward a future where the computer is no longer just a tool to be operated, but a partner in the creative process. The core idea is that instead of providing a fixed set of buttons (GUI) or simply responding with text (LUI), a GenUI builds a bespoke, interactive interface on the fly, tailored to the user's immediate goal. This emerging approach aims to directly address the new gaps created by the LUI.

The Execution-Evaluation Loop

In this new model, the user's primary role shifts almost entirely to the very first stage of Norman's cycle: Form the Goal. The user states a high-level objective ("How is my project's user engagement?"), and the AI performs the initial, complex execution of building a dynamic "sandbox"—an interactive dashboard tailored to that goal.

Once this sandbox is created, the distinction between execution and evaluation dissolves. Every action becomes both at once.

Consider the flow: a user might perceive a downward trend in a chart (an act of evaluation). To interpret this, they click a 'mobile users' filter. This click is not a separate step. It is a seamless fusion of:

- Evaluation: The user is trying to understand the state of the system ("Why is this trend happening?").

- Execution: The click is simultaneously a new expression of intent—a new Perform action—that commands the AI, "Refine the interface to show me this, but only for mobile."

The AI instantly regenerates the interface, leading to a new cycle of perception and interpretation. This rapid loop of Perceive -> Interpret/Refine -> Perceive allows the user to drill down, test hypotheses, and construct their own understanding layer by layer. The "How do I do it?" (Execution) and "What happened?" (Evaluation) problems are solved within the same instantaneous interaction.

This merged process directly confronts the "Gulf of Trust" left by the LUI. The conclusion—"Now I understand my user engagement"—feels earned because the user didn't just receive it; they built it through their own exploration. While evaluation remains partly constrained by the AI's generative process, it transforms from passive judgment into active exploration—the user can probe and verify within the generated interface, even if they cannot fully understand how it was created. While complete trust must be earned by the underlying model's soundness, this interactive loop gives the user the power to probe, verify, and understand for themselves, transforming blind faith into earned trust.

The One Big Idea: Hiding the Hard Stuff

So, what is the real story behind this journey? It all comes down to one idea: abstraction.

Think of it like this: each new change was just a clever way of hiding the computer’s complexity. A command line hides the raw code. A graphical icon hides the command line. And a conversation with an AI hides almost everything.

Crucially, these new layers don't replace what came before; they create new modes of interaction. The command line remains indispensable for developers, just as the GUI is perfect for direct manipulation. Each new stage simply makes computing accessible to more people, for more purposes.

The essential goal of all this work has never changed: to shorten the distance between our intention (what we want to do) and the outcome (seeing it done). The best tools are the ones that let us focus on our ideas, not on the steps we have to take to make them happen.

And now, with AI, abstraction reaches its most radical form: the interface begins to think back.

Imagining the Future: Beyond Today's Interfaces

Where does this journey of abstraction lead? The final step isn't just a better interface, but a fundamentally different kind of partner: a genuine intelligence—whether we call it AGI, ASI, or simply Intelligence when the "artificial" distinction no longer matters.

This presents the ultimate design challenge—the final anchor for the entire field of human–computer interaction. The question is no longer just about making our intentions clear to a predictable tool. The question becomes:

How do we design the interface for an intelligence that may be as complex, or even more complex, than our own?

Suddenly, Norman’s gulfs take on a profound new meaning:

The Execution Gulf becomes an Alignment Gulf.

The problem is no longer "How do I make it do what I want?" but "How do I communicate my intent with the right context, ethics, and constraints, so a super-powerful system doesn't follow my words to a harmful but logical conclusion?"The Evaluation Gulf becomes a Comprehension Gulf.

The problem is no longer "Did it do what I wanted?" but "Can I even understand the solution it has provided?" How do we trust an answer when we can’t fully follow the reasoning behind it?

Designing this final interface is the great work for the next generation. It will be less about pixels and buttons, and more about designing for safety, mutual understanding, and shared goals. The designer’s job will shift from building a bridge across a simple gap to engineering a safe and stable handshake with another mind.